Biggin Hill gets ready for war

7:30am Wednesday 20th July 2011

As part of a News Shopper series exploring the military history of Biggin Hill, DAVID MILLS looks back at the build up to the Second World War.

ON September 30, 1938, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain returned from a meeting with Adolf Hitler, promising “peace for our time”.

In the Munich agreement, after which the term ‘appeasement’ became a dirty word, Hitler promised not to go to war with Britain.

But while cheering crowds saluted Chamberlain with King and Queen at his side at Buckingham Palace, a military base in Biggin Hill was busy preparing for war.

Historian and author Bob Ogley said: “The Munich appeasement brought the station to ‘immediate readiness for war’, code name Diabolo, and all aircraft were ordered to be camouflaged in drab green and brown.

“Each pilot tackled his own machine with paint and brush, obliterating the squadron crest.

“Chamberlain’s announcement was ignored at Biggin Hill.”

By 1939 Biggin Hill was ready.

The aerodrome had been camouflaged, trees planted, windows reinforced and sandbags brought in along with ground defence units.

With the nation still weary from the First World War, another war was unthinkable for most Britons.

But the re-emergence of Germany was becoming an increasing concern.

Mr Ogley said: “In 1936 Hitler introduced his new fully fledged air force, the Luftwaffe, and people began to take notice of the warnings of Winston Churchill (about the German threat).

“Germany was known to be building modern bombers and a fair but alarming assumption at that time was ‘the bomber will always get through’.”

Britain launched its Home Defence Force in May 1936 with Biggin Hill coming under Fighter Command.

Biggin Hill was so successful in establishing ground-to-air and air-to-air communication, it was seen as the perfect place to continue important work developing radar.

Mr Ogley said: “The pilots of 32 Squadron worked unceasingly to perfect new techniques and procedures. Systems were developed which enabled controllers to plot invaders’ exact positions and courses and to direct fighters to intercept them.”

In September 1939 a vociferous opponent to appeasement and the future Prime Minister called by Biggin Hill on his way to Chartwell in Westerham.

With war looming large, Winston Churchill said to officers: “I’ve no doubt you will be as brave and eager to defend your country as were your forefathers.”

The next day, Britain declared war on Germany.

Biggin Hill history: between the wars

8:00am Wednesday 13th July 2011

As part of a News Shopper series exploring the military history of Biggin Hill, DAVID MILLS looks back at the period between the wars.

MUTINY IN THE AIR

By the end of the First World War, Biggin Hill had become a centre for wireless research.

Work was underway on the rebuilding of the site but living conditions for staff were so poor they decided to strike in January 1919.

Around 500 workers lived in tents with no heating or hot water.

Mud was everywhere and the food was rotten.

Historian and author Bob Ogley said: “Some wanted a gentlemanly approach but others sang the Red Flag at the top of their voices and suggested violence. Mutiny was in the air.”

But an RAF investigation sided with the workers and gave them all leave while their camp was improved.

HELLO HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT

In August that year, the progress of the work on wireless technology carried out at Biggin Hill was illustrated in a historic broadcast to a stunned audience in the House of Lords.

The voice of Lieutenant S.G. Newport blared through a loudspeaker: “I am in an aircraft.”

The Under Secretary of State for Air, Major General Seely replied: “Hello Newport. We are the Houses of Parliament. Can you hear us?”

Newport said: “Hello Houses of Parliament. I can hear you well. My pilot can hear you too. We are flying at 8,000ft, 20 miles away.”

So impressed was the government by this major step forward, it set up an Instrument Design Establishment at Biggin Hill to conduct further experiments in long distance flying and landing aircraft in fog.

While residents today complain about the noise from the airport, think of the families living nearby at the time who had to put up with the high pitched sound of a giant concrete disc, designed to guide pilots.

Mr Ogley said: “The deafening noise terrified cattle and shattered windows for miles around.”

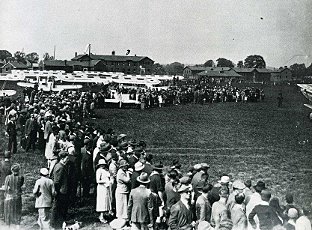

GREAT FUN AT BIGGIN HILL

Building work began in 1927 to extend the airfield following the purchase of 27 acres of land including Cudham Lodge.

On completion five years later, Biggin Hill was home to messes for officers, barracks and married quarters all built in the RAF’s red-brick style, some of which still remain today.

The station reopened and became the base for two fighter squadrons 32 and 23.

Mr Ogley said: “War clouds were not yet looming but the young pilots were encouraged to put in hundreds of hours flying. They played football and cricket at the station and became frequent visitors to the nearby pubs. Life at Biggin Hill in the early 30s was great fun.”

But within a few years, the political landscape in Europe was to change forever and Biggin Hill would be at the heart of Britain’s defence.

How Biggin Hill got pilots talking

7:30am Thursday 7th July 2011

As part of a series charting the military history of Biggin Hill, DAVID MILLS looks back at the birth of one of Britain’s most important fighter stations.

IT was in thick snow on January 2 in 1917 that Lieutenant Dickie and Air Mechanic Chadwick became the first men to land at Biggin Hill.

Less than a year earlier, two subalterns had come across the 75 acre site when looking for a place to build a centre to develop wireless communication.

Biggin Hill historian and author Bob Ogley said: “It was one of the highest points in Kent, 600ft above sea level. What better place to develop a system of communication with pilots in the air?”

The Royal Flying Corps, which became the Royal Air Force in 1918, opened an aerodrome to test equipment which would enable ground to aircraft communication as well as air-to-air.

Mr Ogley said: “The camp buzzed with activity. At times there was high excitement and sheer frustration as something went wrong.

“There were experiments with valves, microphones, receivers, aerials and Biggin Hill was soon festooned with wires.”

The results would change the face of aviation forever.

The landmark moment came in July 1917 when two pilots flying separately in Sopwith 1.5 Strutters spoke to each other, marking the birth of air-to-air telephony at Biggin Hill, something nearly 100 years later we take for granted.

‘A VITAL ROLE IN WORLD PEACE’

Biggin Hill became a major defence site for London in 1917 against German Gotha bombers, which were increasing their raids on the capital.

South London was open to attack and squadrons were brought to Biggin Hill, including No 141, the first operation squadron to be based there.

By Christmas, Biggin Hill had become an operational fighter station and the following March, an officers’ mess, barrack blocks and steel and concrete hangars were built.

The birth of Biggin Hill as a major fighter station was consummated with the first ‘kill’ on the night of May 19, 1918.

Thirty eight Gothas, three Riesen and two smaller planes were crossing the Channel towards the Thames Estuary.

141 Squadron took off in Bristol Fighters to intercept what was the biggest raid of the First World War.

Lieutenants Turner and Barwise were flying 12,000 feet two miles east of Biggin Hill when they saw a Gotha flying above.

Following a deadly pursuit, they shot it down causing it to crash-land at Frinstead, Kent, killing the pilot and navigator.

This became Biggin Hill’s first ‘kill’ as a fighter station.

Mr Ogley said: “It was to be the last air attack of the 1914-18 war. The Germans decided enough was enough. The defences had mastered the bomber and Biggin Hill had played a vital role in world peace.”

THE BIGGIN HILL HERITAGE CENTRE

Campaigners are hoping to open a long overdue military heritage centre on a site next to Biggin Hill airfield to remember The Few who gave their lives for so many.

The centre will chart the groundbreaking development of radar and communication technology used by aircraft during the First and Second World War, as well as house a large collection of artefacts and memorabilia from pilots based at the airfield.

Visit the Biggin Hill Battle of Britain Supporters’ Club, which is the backing the campaign, at bhbobsc.org.uk

Bob Ogley has written two books about the military history of Biggin Hill, ‘Biggin on the Bump’ (£11.99) and ‘Ghosts of Biggin Hill’ (£12.99). For more information and to obtain copies, call 01959 562972 or visit frogletspublications.co.uk

© Copyright 2001-2011 Newsquest Media Group

http://www.newsshopper.co.uk

Such an interesting article and so sad that most people don’t know any of that important information and now Biggin Hill is being treated so appallingly and not listened to!

Long live Biggin Hill!